04.03

23:32

Deep Inside

Recently found a curious article written by Robert Priddy about Jung's unconsciousness interpretation as a 'collective idetation' at http://robertpriddy.com/P/4unconsc.html. The main idea is that the unconscious had been deeply zipped inside before as self-motivating origin. So I'll cite some fragment of the article.

- way a preface + comparison with human unconsciousness and computer analogy:

' he foregoing model of the subconscious mind as a computer-like 'brain' that cannot distinguish of itself between 'positive' and 'negative' or, for that matter between desired/unwanted', 'good/bad', 'virtue/'vice' etc. - is highly misleading for the conscious mind. Not only does the mind, unlike the computer, distinguish physical pleasure from pain, but also supra-physical qualities such as positive and negative 'values'. The capacity of moral discrimination is a function of the human mind, which itself consists in interwoven desires and their many emotional and mental extensions. The mind evaluates, which means that it judges according to deep-seated values that are not systematically codifiable, for in understanding them we depend upon the higher faculty of conscience or 'moral intellect'. The essential character of the human mind here becomes apparent.

The cardinal difference between the human mind and computers evidently lies in motivation. Computers are non-self motivated, whereas the human mind is self-motivating (as discussed elsewhere, this lies in its expression of desires and the consequent possibilities of self-interest, self-control and self-realisation). The subconscious as described here does not itself motivate, but has to be motivated by some stimulus, including a conscious volition. By contrast to the subconscious, the conscious mind, however, is 'self-monitoring' and 'self-programming', as already pointed out.'

some other key fragments:

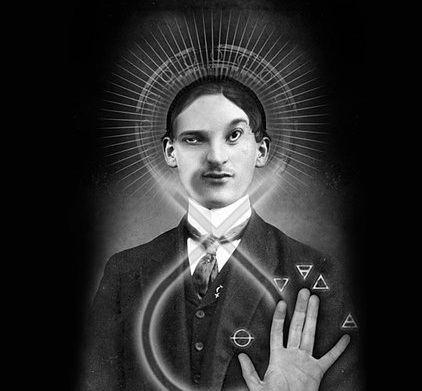

' The idea that there is a fund of universal ideas of a very fundamental sort ('archetypes') are present - and are normally hidden deeply - within all human minds was first forwarded in psychology as the 'collective unconscious' by the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. This theory has many adherents, along with the hypothesis that the collective unconscious exerts powerful influence on human action and hence on the history of the human race. Whether a collective tribal or racial memory does persist ('phylogenetically') in an individual mind, unbeknown to the person concerned, is an open question, no less than the question how this may be possible. This fund is supposedly handed down from our forbears, possibly genetically or perhaps by other means not known to science.

The collective unconscious and its related ideas (archetype, individuation etc.) have been most difficult to define in practically-relevant terms or in ways that open for clear empirical testing. Nor is it by any means easy to evaluate whether knowledge about the collective unconscious leads to reliable methods with proven practical benefits in therapy. Jung made no secret that he believed the operations of the collective unconscious to be mysterious and beyond normal rational analysis or investigation.

Jung's overall view of the unconscious retains the Freudian assumption that it represents what we are ignorant of regarding our psychic selves. This includes the darker or 'shadow' aspects: untransformed 'negative' traits in a person. Jung saw this 'shadow' as a hindrance to be dealt with as a preliminary of the 'individuation process'. This latter led to supra-personal 'knowledge' and transcendental states of awareness. Jung held that few persons are aware of these kind of experiences, which arise naturally only as a result of the mature process of 'individuation'. Individuation implies freedom from the sway of all aspects of the human 'herd instinct' as laid down in the collective unconscious. It involves a degree of realisation of oneself as an autonomous self-determined being and as such represents a kind of individualism. Because the process apparently works through intensely personal and unique configurations of experience, it is evidently not easy to generalise about it in accurate or precise enough ways to be practically informative. This fact is well demonstrated by the Jungian literature itself, which tends towards symbolic obscurity and often cites case histories in abstract, taken out of any specific context of social and personal situations.

Critics of Jung point out how his devaluation of rational thought affects people's concentration of their attention to distinguish their thoughts. The Jungian approach often involves less analysis then mystique, as in a religion. Jung's psychology was developed, as he himself recounts, as an alternative to the strict and narrow religious precepts of his priestly father, against which he revolted. The approach to something beyond human limitations through a theory of psychic development makes religious symbolism more palatable to those who have lost faith, and eventually approaches questions concerning divinity and God from a liberal scientific and agnostic humanistic starting point.'

- way a preface + comparison with human unconsciousness and computer analogy:

' he foregoing model of the subconscious mind as a computer-like 'brain' that cannot distinguish of itself between 'positive' and 'negative' or, for that matter between desired/unwanted', 'good/bad', 'virtue/'vice' etc. - is highly misleading for the conscious mind. Not only does the mind, unlike the computer, distinguish physical pleasure from pain, but also supra-physical qualities such as positive and negative 'values'. The capacity of moral discrimination is a function of the human mind, which itself consists in interwoven desires and their many emotional and mental extensions. The mind evaluates, which means that it judges according to deep-seated values that are not systematically codifiable, for in understanding them we depend upon the higher faculty of conscience or 'moral intellect'. The essential character of the human mind here becomes apparent.

The cardinal difference between the human mind and computers evidently lies in motivation. Computers are non-self motivated, whereas the human mind is self-motivating (as discussed elsewhere, this lies in its expression of desires and the consequent possibilities of self-interest, self-control and self-realisation). The subconscious as described here does not itself motivate, but has to be motivated by some stimulus, including a conscious volition. By contrast to the subconscious, the conscious mind, however, is 'self-monitoring' and 'self-programming', as already pointed out.'

some other key fragments:

' The idea that there is a fund of universal ideas of a very fundamental sort ('archetypes') are present - and are normally hidden deeply - within all human minds was first forwarded in psychology as the 'collective unconscious' by the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. This theory has many adherents, along with the hypothesis that the collective unconscious exerts powerful influence on human action and hence on the history of the human race. Whether a collective tribal or racial memory does persist ('phylogenetically') in an individual mind, unbeknown to the person concerned, is an open question, no less than the question how this may be possible. This fund is supposedly handed down from our forbears, possibly genetically or perhaps by other means not known to science.

The collective unconscious and its related ideas (archetype, individuation etc.) have been most difficult to define in practically-relevant terms or in ways that open for clear empirical testing. Nor is it by any means easy to evaluate whether knowledge about the collective unconscious leads to reliable methods with proven practical benefits in therapy. Jung made no secret that he believed the operations of the collective unconscious to be mysterious and beyond normal rational analysis or investigation.

Jung's overall view of the unconscious retains the Freudian assumption that it represents what we are ignorant of regarding our psychic selves. This includes the darker or 'shadow' aspects: untransformed 'negative' traits in a person. Jung saw this 'shadow' as a hindrance to be dealt with as a preliminary of the 'individuation process'. This latter led to supra-personal 'knowledge' and transcendental states of awareness. Jung held that few persons are aware of these kind of experiences, which arise naturally only as a result of the mature process of 'individuation'. Individuation implies freedom from the sway of all aspects of the human 'herd instinct' as laid down in the collective unconscious. It involves a degree of realisation of oneself as an autonomous self-determined being and as such represents a kind of individualism. Because the process apparently works through intensely personal and unique configurations of experience, it is evidently not easy to generalise about it in accurate or precise enough ways to be practically informative. This fact is well demonstrated by the Jungian literature itself, which tends towards symbolic obscurity and often cites case histories in abstract, taken out of any specific context of social and personal situations.

Critics of Jung point out how his devaluation of rational thought affects people's concentration of their attention to distinguish their thoughts. The Jungian approach often involves less analysis then mystique, as in a religion. Jung's psychology was developed, as he himself recounts, as an alternative to the strict and narrow religious precepts of his priestly father, against which he revolted. The approach to something beyond human limitations through a theory of psychic development makes religious symbolism more palatable to those who have lost faith, and eventually approaches questions concerning divinity and God from a liberal scientific and agnostic humanistic starting point.'